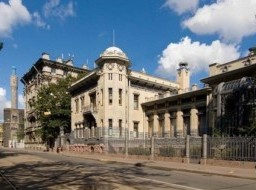

Yusupov Palace

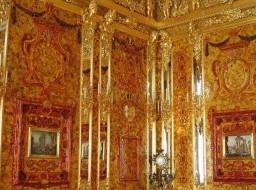

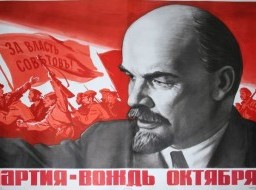

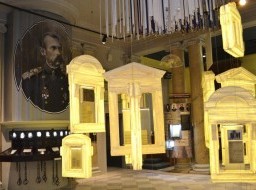

The spectacular Yusupov Palace on the Moyka River has some of best 19th-century interiors in the city, in addition to a fascinating history. Five generations of elite aristocratic dynasty Yusupov were the owners of the palace on the Moika from in St. Petersburg from 1830 to 1917. It was famous not only by its architectural design, but also by the frequent and sumptuous receptions, including dances and masquerades. The palace's last owner was the eccentric Prince Felix Yusupov, a high-society darling and at one time the richest man in Russia. The palace is famous for the murder scene Grigory Rasputin - Siberian peasant who became a beginning of XX century spiritual mentor and family friend Emperor Nicholas II. The place where Grigory Rasputin was murdered in 1916, and the basement where this now plot unravelled can be visited as part of a guided tour.  Also known as the Moika Palace, the Yusupov Palace is located on the famous Moika Embankment in the very center of St. Petersburg The most sumptuous non-imperial palace in St. Petersburg was the home of the unabashedly rich and powerful Yusupov family, who from the mid-18th century (when the first version of this palace was built) until the Revolution, moved in the most powerful circles in Russia. The palace was built by Vallin de la Mothe in the 1770s, but the current interiors date from a century later, when it became the residence of the illustrious family. The palace interiors are sumptuous and rich, with many halls painted in different styles and decked out with gilded chandeliers, silks, frescoes, tapestries and some fantastic furniture. In addition to being movers and shakers, the Yusupovs were great collectors of art, and their collection was known well beyond Russia. After the Revolution, most of the collection was moved to the Hermitage, making this place just another palace, though traces of the incredible wealth that once kept this place pulsating with life still remain: the various sitting rooms, the intricate chandeliers and candelabras that adorn every room and corridor, and the beautiful private theater that looks like a cozy version of the Mariinsky. In 1726, Peter the Great's niece — Tsaritsa Praskovia Ivanovna — gave her small manor, situated on the left bank of the Moika river, to the Semenov Regiment of the Russian Imperial Guard, where they quartered until 1742. In mid-1740s, this area became part of a big manor owned by the adroit courtier count Peter Shuvalov. Peter Shuvalov's son, count Andrei Petrovich, sold his father's mansion. Peter was a glamorous grandee and a minion of Catherine II in the epoch of the new emperor and probably thought that his parent's mansion was old-fashioned and archaic. Yusupov Palace on Moika became the Yusupovs' family residence in 1820 and until Bolshevik Revolution remained the richest aristocratic house of Russia. The Palace was nationalised by decree as of 22 February 1919. Commission on Museums Affairs of the Commissariat of Enlightenment decided to preserve the Yusupov Palace and turn it into an artistic and historic monument. On 20 September 1919, the Yusupov Gallery was opened to visitors, and was exhibiting works of arts from the family collection. In 1924, tours were launched into the rooms where Grigory Rasputin was murdered. Unfortunately, the period when the artistic treasures of the Yusupovs were accessible to visitors within their home environment turned out to be very short. In 1925, the museum of "noble life" in the Yusupov Palace was closed, along with a few other museum mansions as well. So began its liquidation that is the erratic and sometimes uncontrolled removal of the more valuable works of art and items of decor.  Did you know? - Yusupov Palace has a permanent exhibition demonstrating the last evening of Grigori Rasputin Despite the deep post-revolution shocks, the Yusupov Palace's fate turned out to be more fortunate than that of many other antique mansions. After the museum was closed, the Palace was handed over to pedagogical intelligentsia of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), becoming its centre of professional and creative communication. Because of that, the palace wasn't used quite as barbarically and thoughtlessly as other "monuments of noble life" and its gala and private halls have survived to this day. During the Great Patriotic War the mansion on Moika River shared the same tough fate as the rest of city on Neva River. During the blockade an evacuation hospital was located here. The building was heavily damaged by bombing and artillery fire. Large-scale reconstruction of halls damaged during the blockade began the first postwar year. In 1960, the Yusupov Palace was granted the status of a federal historic and cultural monument.

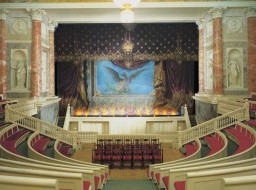

The Yusupovs were one of Russia's wealthiest families. They even had their own private theater Reconstruction of the palace and manor continues to this day. Thanks to the implementation of a purposeful scientific restoration program some visitors can now access the gala halls on the second floor, the Art Gallery suite, the nonpareil Home Theatre, the so-called parents' half: private rooms of the prince and elegant boudoirs of the princess, suite of formerly private rooms of Felix Yusupov where "The Murder of Grigory Rasputin" historical folk exhibit has been created, and the living rooms of Irina and Felix Yusupovs with recreated interior decor and a historical documentary exhibit "History of the Yusupovs. 10th – 21st centuries". Nowadays the Yusupov Palace is a unique "monument to noble life". This is the mansion where one of the most eminent and richest aristocratic families in Russia lived for nearly a century. It has a lot to tell of the tastes, fancies and fantasies of its former owners and the nobility's everyday life in general. The 2nd floor features an amazing ballroom (the White Column Room), banquet hall, the delightful Green Drawing Room and the ornate rococo private theatre. On the ground floor you will see the fabulous Turkish Study (used by Felix as a billiards room), the Prince's study and the Moorish Drawing Room, among many other rooms. Even in the absence of its art and sculpture attire, the palace still leaves a great artistic impression and surprises with its lively homeliness and how tended it is. |

|